Who among us hasn’t pissed off that grumpy old man on the road in his youth? In some cases you can't help it because some people are simply not suited to live in the suburbs and will scare the neighbours' children by roaring “Get out of my garden!” At any time, an unsuspecting little one could set foot on their prized possession. By doing this, they set a goal for themselves when it's time to deliver toilet paper to someone else's home or to a jingle. No one expected that the witch next door would make good on her threat.

Director Gita Ganderbilt's self-contradictory title “Good Neighbors” centers on the shocking case of Susan Lorinz, a whiny Florida girl who was convicted of Trespassing with a grudge against Clint Eastwood. It's such a flippant approach to depicting a real-life tragedy that resulted in the death of African-American single mother Ajik “AJ” Owens, but the movie goes some way to endorsing the violent alternative. Not this time, and it turned on the collective protests of locals upset that the confused white gunman was not being tried in the same way as a black man.

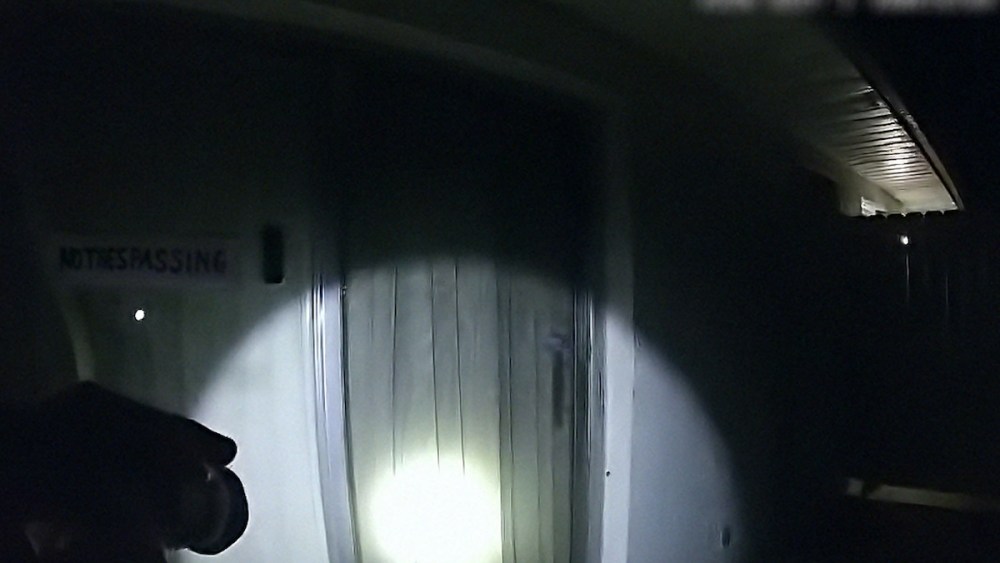

Ganderfield's taut true-crime documentary recreates the dispute—from the first 9/11 names to the final court verdict—everything formally contemporary, philosophically necessary, and almost entirely sourced. Of the official footage, much of it was taken from police body cameras. The thriller that follows unfolds like a cross between “Paranormal Practice” and “Watch It's Over,” leaving the viewer free to draw their own conclusions from the evidence on camera. (The availability of such material, which would revolutionize true-crime filmmaking, also includes the Oscar-nominated, New Yorker-produced quickie documentary “The Incident.”)

As unfair as it is, the legal norms of self-defense and “stand your ground” have long been used to excuse murderers whose deep-seated (and sometimes uncensored) racism demeans the victims they view as monstrous or inferior. life. That's one of the many subtexts embedded in this emotional, thought-provoking social experiment from the Emmy Award-winning director of “Lownds County and the Black Energy Trail,” and his film is a touchstone for audiences. 'Personal bias.

Among its many levels, Ganderbilt's wonderful career is a surprisingly resonant look at the irreconcilable differences between neighbors – a situation constantly discussed on trashy daytime television but rarely embraced in public Described in the movie Dear. Such conflicts often do not resolve themselves and can often escalate to a retaliatory or even fatal outcome (my accomplice once had his car's brake pull minimized by a man next door who was working illegally in a noisy auto repair shop .).

Ironically, it was Lorinz (of potentially harmful celebration) who kept calling 911. Police first responded in February 2022, swooping out to interview various neighbors after Lorinz accused Owens of giving her a “no trespassing” signal. Unlike traditional documentary strategies, Ganderhill does not conduct live interviews or attempt to recreate events, but instead uses police body camera footage to describe the events. “That girl always annoys other people's kids,” one neighbor said, pointing to an empty lot where black and white children liked to ride horses, much to the annoyance of their home-working neighbors. “She's bossy,” said one young woman, who viewed Lorinz as an offended “Karen.”

Sociologically speaking, the Karen phenomenon—where white girls use their social status and privilege to dictate and demand how others behave—would be difficult to pin down because it operates on invisible dynamics. It’s no secret that black people are at a much greater risk of being accidentally (or even intentionally) shot by police. Did Lorinz understand she could endanger her neighbor's life every time she called 911? Could it be that she relied on it? Weaponization of police by some residents remains one of many undisclosed tactics the agency uses to enforce not just legislation but the remnants of white supremacy.

What we don't know from “Good Neighbors” is what's going on in Lorinz's brain when the local kids are so noisy that she can't focus. Multiple police interviews revealed she yelled the “N” word and different nicknames at her petty tormentors. However, footage from her personal security camera showed the children deliberately taunting her, shaking their butts as she went.

All of this was done without being witnessed by the police, whose every word was recorded (as well as choice phrases explaining Lorinz, who came across as even more obnoxious than her neighbors). By the time police arrived, every name had been identified and a crime had been settled — but not that any of it justified what ultimately happened, with Lorintz firing a gun into the incident.

This was the trickiest part for Ganderhill to recreate, as the filming took place off-camera, although the director did use audio recorded from doorbell cameras throughout the road to show the audience a way in which the confrontation – from a distance – The life-or-death situation Lorinz describes is entirely different.

Unfortunately, there is no direct answer to this disagreement. Still, one would be surprised why the volatile tenant – who claimed he had a right to “the peaceful and quiet enjoyment of his property” – sought to restrain police in the first place. That, coupled with the role of weapons in her response, should give viewers plenty of debate and debate. Meanwhile, body camera footage reveals Lorinz's most insidious tactics: the way she distorted events and tried to control authority figures once they arrived. For all the criticism we have traditionally leveled at the police these days, they, like the great ones here, have hope. Had Owens been the only one to say their names that fateful night, the question might have turned out differently.

Post Revolutionary doctor uses body camera footage first appeared in all celebrities.